LockBit is a prolific family of ransomware that operates under the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model [1,2], which can be considered a part of the Malware-as-a-Service model [3]. The group has been active since around 2019, and it has grown to become one of the most widespread and disruptive ransomware threats. In this RaaS scheme, the core LockBit developers lease their ransomware to affiliates, other cybercriminals who carry out the intrusions, in exchange for a share of the profits. Notably, LockBit was reported as the most deployed ransomware globally in 2022 [4], with victims across many sectors (finance, government, healthcare, etc.). Despite some variation in tactics by different affiliates, LockBit attacks typically follow a similar multi-stage pattern involving initial access, lateral movement, data exfiltration, file encryption, and a double extortion strategy. The double extortion strategy implies stealing sensitive data before encrypting victim systems to increase the pressure on its victims to pay. This means that even if victims can restore their files from backups, the attackers can threaten to publish the stolen data unless a ransom is paid [5].

The group has been hunted down by several initiatives, e.g., operation Cronos [6], and several leaks, nonetheless, it keeps reviving from its ashes. As a result, the group manages to find affiliates to penetrate hosts and infect the victims with their ransomware.

A recent leak of the database used by the panel that is used by the group sheds some light on their operations that we will present in this series of blog posts. Based on the MySQL dump that has appeared on their onion sites, the leak appears to have happened on April 29, 2025, at 05:26 PM, and has allegedly been performed by someone from Prague.

The leak contains:

- the users of the panel (including their registration, last login, and password in clear text)

- the negotiations with their victims

- the configurations of their builds

- their victims and login activity

- the bitcoin addresses they had preallocated

- some news related to their operations

- keys

- error messages on their platform

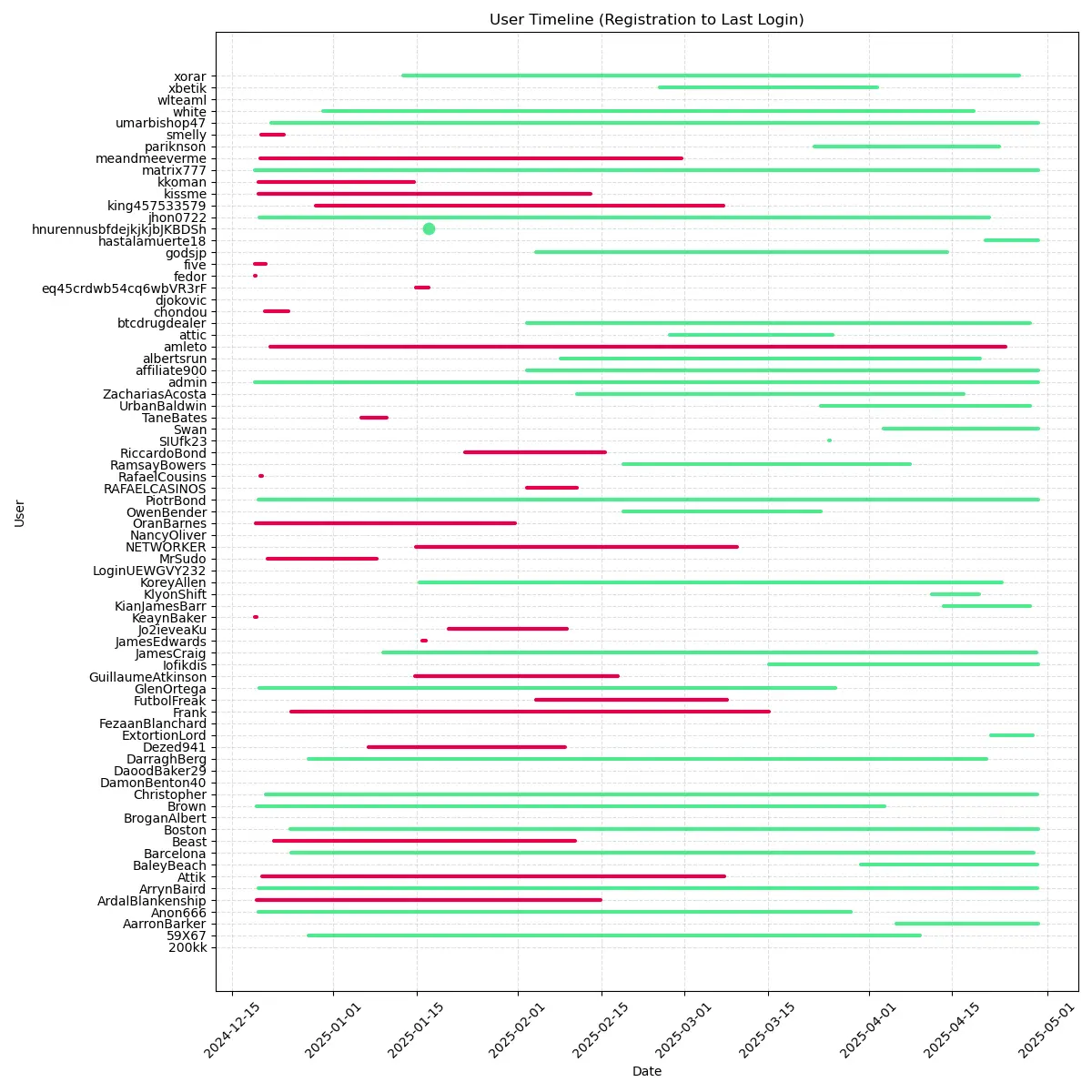

First, let’s see the login activity of the users. In green, we have the active users, and in red, we have the ones that have been paused.

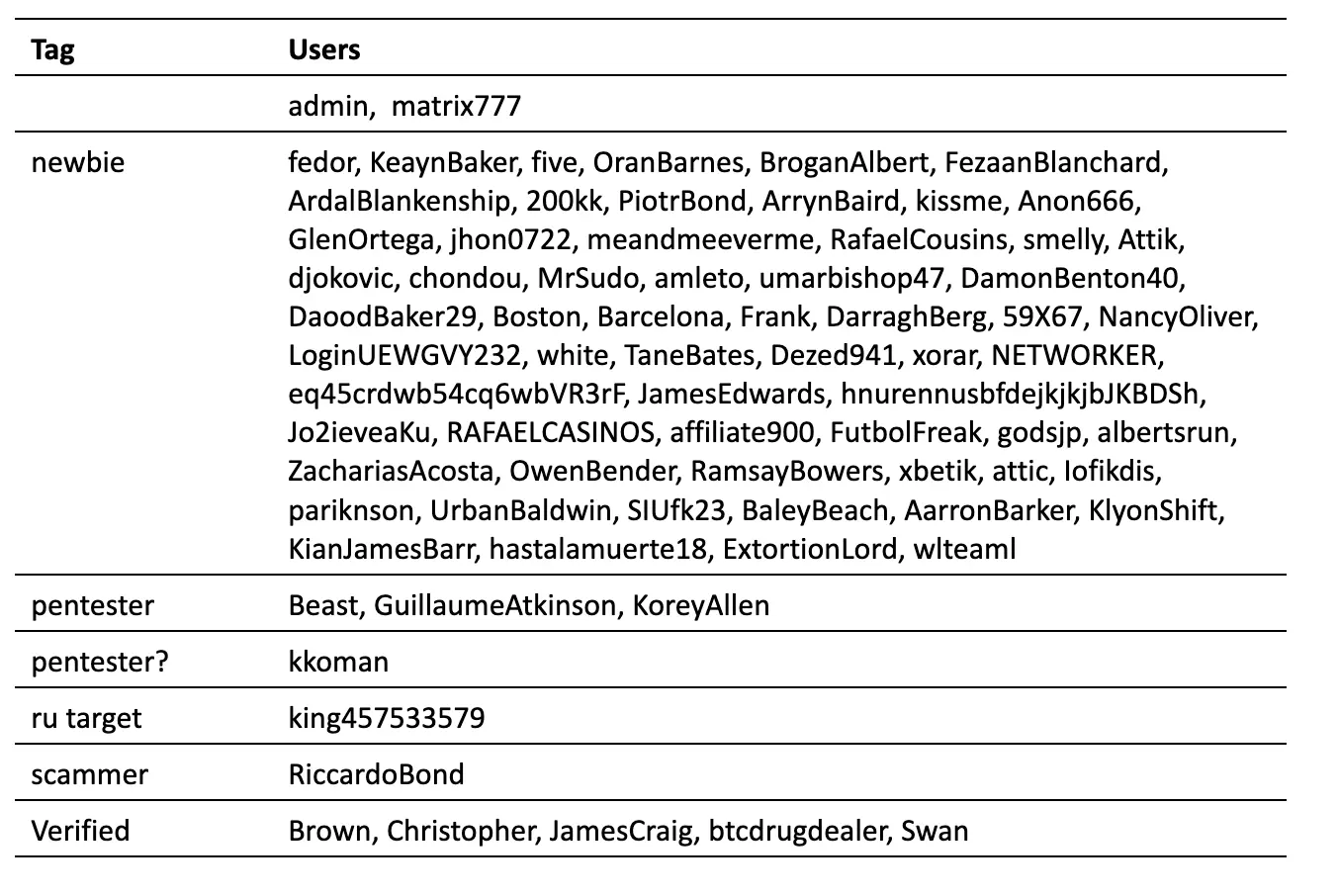

Additionally, the users are classified with tags as follows:

Interestingly, from the tags, we can observe that one user (king457533579) is assigned a Russian target.

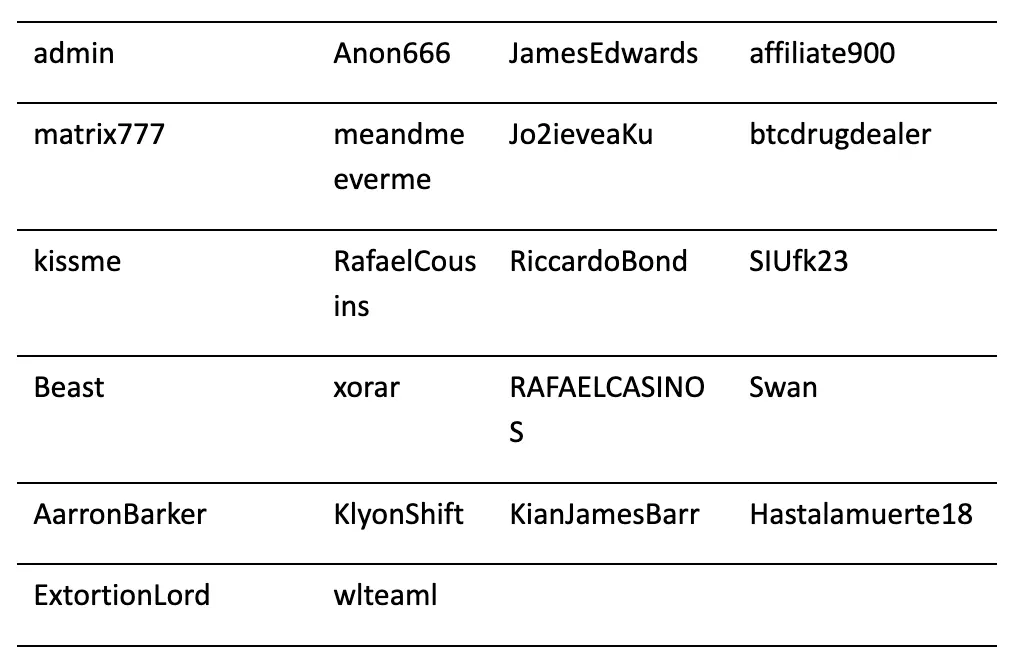

Moreover, the following users use Tox, whose ID has been leaked:

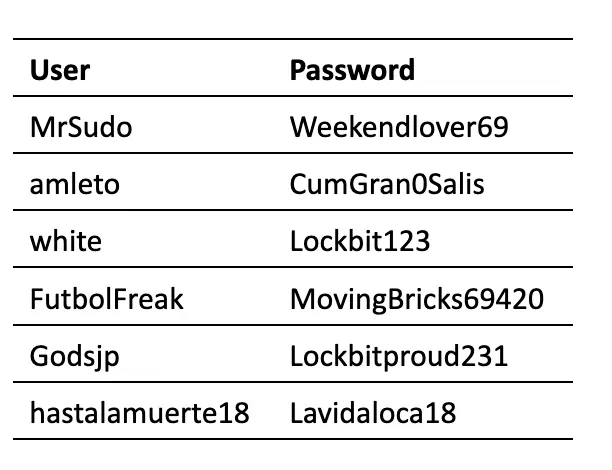

As referred to above, the passwords are stored in the database in clear text format. Despite this being a very poor practice, it is also evident that some affiliates use very sloppy passwords:

From the old list of affiliates [7], the new affiliates that seem to have rejoined are the following:

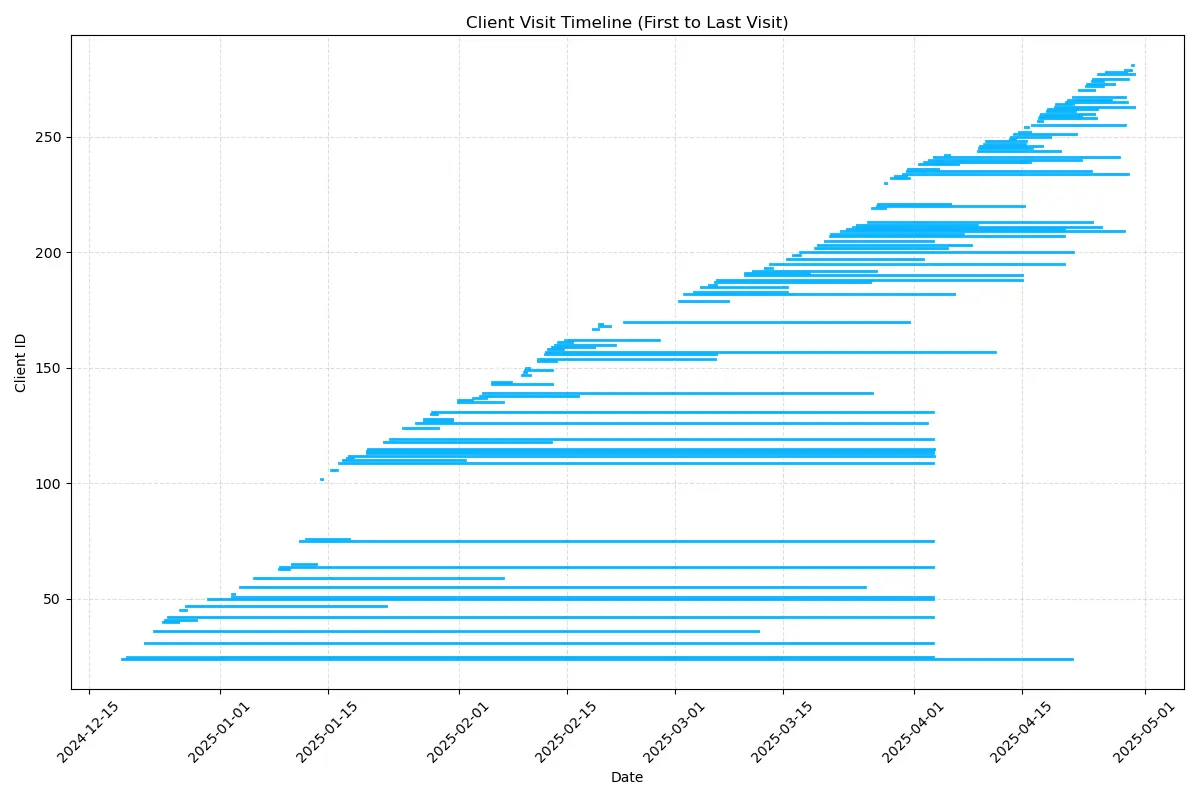

The figure below depicts the period during which victims visited the platform.

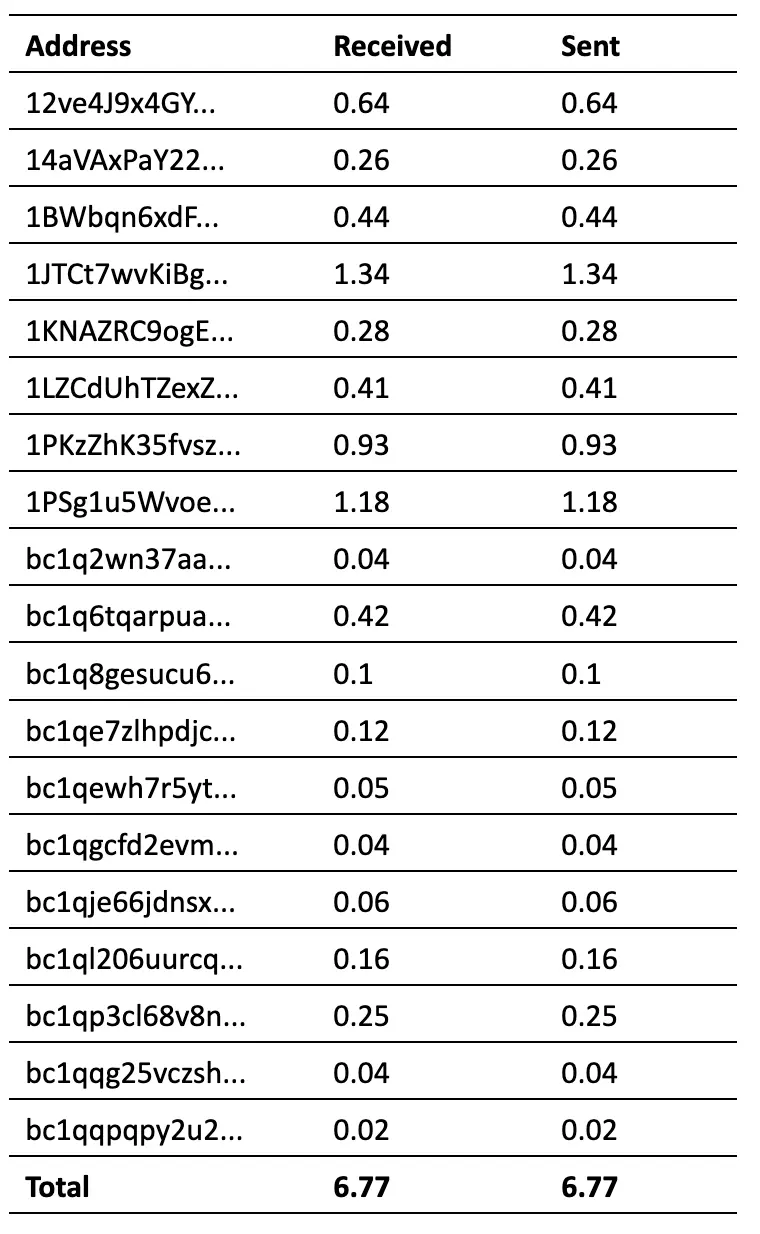

The database shows that Lockbit had 246 victims in their database, of which 239 logged into the platform, and 208 interacted in the chats. However, as shown in the chats, only 19 bitcoin addresses appear and received Bitcoins in the chats in exchange for decryption software and/or the assurance that their stolen data will be deleted safely from Lockbit servers and would not be published.

Based on the current price of Bitcoin, the above is on the scale of €620115.97. The latter implies that there is a steep decline in Lockbit’s operations, compared to the outcomes of the Cronos operation [6]. The group had 194 affiliates in February 2024 [7] and now has 75, most of which are characterised ‘newbies’, showing that the stuffing process has not gone so well for them, as the leaks and take downs have raised distrust. Moreover, the earnings are a small fragment of what the group used to make [8], which can be attributed to low-profile victims, low impact on the victims, or even efficient decryptors, which can mitigate the attack; for instance No More Ransom [9] has one for Lockbit 3.0.

The above illustrates that even big ransomware groups use poor cybersecurity measures and practices. Moreover, it shows that organisations that give in to the ransom threats might afterwards be leaked, so paying the ransom does not cover the impact.

In the next blog posts, we will analyse the leaks further and provide more detailed insights.

Authors: Constantinos Patsakis, Athena Research Center; Anargyros Chrysanthou, V4ensics.

References

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/ransomware/ransomware-as-a-service-raas/

- Meland, Per Håkon, Yara Fareed Fahmy Bayoumy, and Guttorm Sindre. “The Ransomware-as-a-Service economy within the darknet.” Computers & Security 92 (2020): 101762.

- Patsakis, Constantinos, David Arroyo, and Fran Casino. “The Malware as a Service ecosystem.” Malware: Handbook of Prevention and Detection. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024. 371-394.

- https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-165a

- https://www.trendmicro.com/vinfo/us/security/news/cybercrime-and-digital-threats/ransomware-double-extortion-and-beyond-revil-clop-and-conti

- https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/law-enforcement-disrupt-worlds-biggest-ransomware-operation

- https://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/the-nca-announces-the-disruption-of-lockbit-with-operation-cronos

- https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/aa23-165a_understanding_TA_LockBit.pdf

- https://www.nomoreransom.org/